Thursday, May 18, 2017

YAAC ("yet again about copyright")

Some sensible remarks from the Director of UofA's copyright office. Importantly, the UofA relinquishes its rights to the copyright of work written by faculty members. Faculty members own the copyright of their writings.

Monday, May 15, 2017

IBUS bug fix ... again (sigh!)

Further to https://cikitsa.blogspot.ca/2012/01/ibus-bug-fix.html, I found the same bug cropping up in Linux Mint 18.1, with IBUS 1.15.11.

Some applications don't like IBUS + m17n, and certain input mim files. For example, LibreOffice and JabRef. Trying to type "ācārya" will give the result is "ācāry a". And in other strings, some letters are inverted: "is" becomes "si" and so forth.

Here's the fix.

Create a file called, say ibus-setting.sh with the following one-line content:

Phew!

This fixes the behaviour of IBUS + m17n with most applications, including LibreOffice and Java applications like JabRef. However, some applications compiled with QT5 still have problems. So, for example, you have to use the version of TeXStudio that is compiled with QT4, not QT5. [Update September 2018: QT5 now works fine with Ibus, so one can use the QT5 version of TeXstudio with no problem.]

Some applications don't like IBUS + m17n, and certain input mim files. For example, LibreOffice and JabRef. Trying to type "ācārya" will give the result is "ācāry a". And in other strings, some letters are inverted: "is" becomes "si" and so forth.

Here's the fix.

Create a file called, say ibus-setting.sh with the following one-line content:

export IBUS_ENABLE_SYNC_MODE=0Copy the file ibus-setting.sh to the directory /etc/profile.d/, like this:

sudo cp ibus-setting.sh /etc/profile.dMake the file executable, like this:

sudo chmod +x /etc/profile.d/ibus-setting.shLogout and login again.

Phew!

This fixes the behaviour of IBUS + m17n with most applications, including LibreOffice and Java applications like JabRef. However, some applications compiled with QT5 still have problems. So, for example, you have to use the version of TeXStudio that is compiled with QT4, not QT5. [Update September 2018: QT5 now works fine with Ibus, so one can use the QT5 version of TeXstudio with no problem.]

Wednesday, March 22, 2017

Dvandva compounds of adjectives

Some discussions supporting the existence of this formation:

- Speyer, Sanskrit Syntax, para 208

- Whitney, para 1257

- Burrow, The Skt Language, p.219

Monday, January 09, 2017

Tuesday, October 04, 2016

Crowd-sourcing peer-review

PeerJ continues to push the envelope. Fascinating concept of crowd-sourcing refereeing.

Thursday, September 29, 2016

What's the point of an academic journal?

Presuppositions

I find that I often read my academic colleagues' papers at academia.edu and other similar repositories, or they send me their drafts directly. I am not always aware of whether the paper has been published or not. Sometimes I can see that I'm looking at a word-processed document (double spacing, etc.); other times the paper is so smart it's impossible to distinguish from a formally-published piece of writing (LaTeX etc.).Reading colleagues' drafts gives me access to the cutting edge of recent research. Reading in a journal can mean I'm looking at something the author had finished with one, two or even three years ago. In that sense, reading drafts is like attending a conference. You find out what's going on, even if the materials are rough at the edges. You participate in the current conversation.

In many ways, reading colleagues' writings informally like this is more similar to the medieval ways of knowledge-exchange that were dominated by letter-writing. The most famous example is Mersenne (fl. 1600), who was at the centre of a very important network of letter-writers, and just preceded the founding of the first academic journal, Henry Oldenberg's Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (founded 1665).

What am I missing?

Editorial control

What I don't get by reading private drafts is the curatorial intervention of a board of editors. A journal's editorial board acts as a gatekeeper for knowledge, making decisions about what is worth propagating and what is not worth propagating. The board also makes small improvements and changes to submissions, required since many academic authors are poor writers, and because of the natural processes of error. So, a good editorial board makes curatorial decisions about what to display, and improves quality.Counter-argument: Many editorial boards don't do their work professionally. The extended "advisory board members" are window-dressing; the real editorial activity is often carried out by only one dynamic person, perhaps with secretarial support. This depends, of course, on the size of the journal and the academic field it serves. I'm thinking of sub-fields in the humanities.

Archiving and findability

A journal also provides archival storage for the long term. This is critically important. An essential process in academic work is to "consult the archive." The archive has to actually be there in order to be accessed. A journal - in print or electronically - offers a stable way of finding scholars' work through metadata tagging (aka cataloguing), and through long-term physical or electronic storage. If I read a colleagues' draft, I may not be able to find it again in a year's time. Is it still at academia.edu? Where? Did I save a copy on my hard drive? Is my hard drive well-organized and backed up (in which case, is it a journal of sorts?)?Counter-argument: Are electronic journals archival? Are they going to be findable in a decade's time? Some are, some aren't. The same goes for print, but print is - at the present time - more durable, and more likely to be findable in future years. An example is the All India Ayurvedic Directory, published in the years around the 1940s. A very valuable document of social and medical history. It's unavailable through normal channels. Only a couple of issues have been microfilmed or are in libraries. Most of the journal is probably available in Kottayam or Trissur in Kerala, but it would take a journey to find it and a lot of local diplomatic effort to be given permission to see it. Nevertheless, it probably exists, just.

Prestige

A journal may develop a reputation that facilitates trust in the articles published by that journal. This is primarily of importance for people who don't have time to read for themselves and to engage in the primary scholarly activity of thinking and making judgements based on arguments and evidence. A journal's prestige may also play a part in embedding it in networks of scholarly trust and shared but not known knowledge, in the sense developed by Michael Polanyi (Personal Knowledge, The Tacit Dimension and other writings).Conclusion

At the moment, I can't think of any other justifications for the existence of journals. But if editorial functions and long-term storage work properly, they are major factors that are worth having.Further reading

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Academic_journal#New_developments

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scholarly_communication

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Serials_crisis

Tuesday, July 26, 2016

Getting Xindy to work for IAST-encoded text

Update, 2021

January 2021. Since writing about Xindy below in 2016, a new indexing program has been released, Xindex by Herbert Voß. I now use xindex with this configuration file for IAST sorting. My preamble says

\usepackage[imakeidx]{xindex}

\makeindex[name=lexical,

title=Lexical Index,

columns=3,

options= -c iast -a -n, % nocasesensitive, noheadings

]

Wednesday, June 08, 2016

How "open" is "Open Access"

As the Open Access model becomes increasingly important for public knowledge dissemination, some agencies with vested interests have begun to complicate matters by introducing hybrid publishing models. Some of these are not fully in the interests of authors or readers.

PLOS has a great discussion about the issues at stake, and they refer to the OAS brochure, which is provided in many languages.

The second page of this OAS brochure is very short, clear and helpful. Recommended!

PLOS has a great discussion about the issues at stake, and they refer to the OAS brochure, which is provided in many languages.

The second page of this OAS brochure is very short, clear and helpful. Recommended!

Friday, April 22, 2016

On the use of parentheses in translation

This

deserves a fuller discussion; I'm just doing a quick note here, arising out of a conversation with Dagmar and Jason Birch.;

My thinking is influenced by my teachers Gombrich and Matilal, both of whom had a lot to say about translation, and by reading materials on translation by Lawrence Venuti and Umberto Eco (Mouse or Rat?). There's a huge literature on translation, including specific materials on Skt like Garzilli, E. (Ed.) Translating, Translations, Translators from India to the West. Cambridge, MA, Harvard Univ., 1996.

I wonder about the heavy use of parentheses by Indologists. One does not see this in English translations from French, say, or German. Or even Latin or Greek. What are we up to? I can distinguish several reasons for parentheses in English trs. from Skt.

The Kielhorn exemplifies another major problem, that Matilal used to talk about passionately. If you read Kielhorn's tr. leaving out the parentheses, it's gobbledegook. Matilal said that if one has to use parentheses, then the text not in parentheses should read as a semantically coherent narrative. This is because the Sanskrit is a semantically coherent narrative. To present an incoherent English text is a tacit assertion that the Sanskrit is incoherent. In which case, we should see parentheses in Sanskrit too. Sometimes we do, as in Panini's mechanism of anuvṛtti, when parts of previous sutras are tacitly read into subsequent ones. Anuvṛtti is doing similar work to that done by parentheses. So Vasu's translation of Panini uses parentheses in a valid way, I would argue.

What are valid reasons for parentheses? I would say that very, very rarely it is justified to put a Skt word in brackets when not to do so would be seriously confusing or misleading for the typical reader, or when the Skt author is making a tacit point. "He incurred a demerit (karma) by failing to do the ritual (karma)." Or, in the RV, "The lord (asura) of settlements has readied for me two oxen ."(Scharfe 2016: 48).

Then there's the psychology of reading. For me, this is one of the important reasons for not using parentheses or asides of any kind. I've never articulated this before, so what follows may be a bit incoherent. When I watch my mind during reading, I absorb sentences and they create a sense of understanding. It's quite fast, and it's a flow. As I go along, the combination of this flow of sentences and the accumulation of a page or two of it in memory produces the effect of having a new meaning in my mind, of having understood a semantic journey shared with me by the author. But when there are many parentheses, that flow is broken. The reading becomes much slower, and I often have to read things several times, including a once-over skipping the parentheses. This slow, assembly-style reading is not impossible, and one may gain something. But one loses a lot. What's lost is the larger-scale comprehension, and the sense of a flow of ideas.

What I find works for me as a reader and writer is to avoid the branching of the flow of attention while reading. Branching is often done through parenthetical statements, -- and through dashed asides -- (and through discursive footnotes), but not citation footnotes. In my mind, it's like travelling in a car and taking every side road, driving down it for two hundred metres and then coming back to the main road, and continuing just until the next side road, etc. As a writer, I find it quite easy to avoid branching. I do it by thinking in advance about the things I want to say, and then working out a sequence in which I want to present them so that the reader gets the sense of connection. Cut-n-paste is very helpful.

I'm not sure whether the above is totally personal to me, or a widely-shared phenomenon. I've never read anything about this topic. I have read about eye-movements during reading, and the relationship of this to line-length and typeface design. I should look around for material on the psychology of comprehension during reading. There must be something out there.

Wendy Doniger, who writes well, said last year:

References

My thinking is influenced by my teachers Gombrich and Matilal, both of whom had a lot to say about translation, and by reading materials on translation by Lawrence Venuti and Umberto Eco (Mouse or Rat?). There's a huge literature on translation, including specific materials on Skt like Garzilli, E. (Ed.) Translating, Translations, Translators from India to the West. Cambridge, MA, Harvard Univ., 1996.

I wonder about the heavy use of parentheses by Indologists. One does not see this in English translations from French, say, or German. Or even Latin or Greek. What are we up to? I can distinguish several reasons for parentheses in English trs. from Skt.

- Fear. We are asserting to the reader that we know what we're doing, and making our word-choices explicit. This is a defence against the small voice in our brains that says "professor so-and-so won't accept a fluent, uninterrupted translation from me, seeing it as bad. I'll get criticised in public."

- Habit. We see others doing it and absorb the habit.

- Germanism. Venuti has shown compellingly, in The Translator's Invisibility, how different linguistic audiences receive translations differently. English readers and reviewers approve strongly of translations of which they can say, "it reads as naturally as if the author had written in English." German readers are different, and want to experience a sense of foreignness in their translations; if a translation reads fluently in German, they feel there is some deception being carried out. Since so many translations from Sanskrit were done by Germans, English readers like us get used to the "German" presuppositions of the nature of translation, and simply carry on in that idiom. See the attached Kielhorn example.

The Kielhorn exemplifies another major problem, that Matilal used to talk about passionately. If you read Kielhorn's tr. leaving out the parentheses, it's gobbledegook. Matilal said that if one has to use parentheses, then the text not in parentheses should read as a semantically coherent narrative. This is because the Sanskrit is a semantically coherent narrative. To present an incoherent English text is a tacit assertion that the Sanskrit is incoherent. In which case, we should see parentheses in Sanskrit too. Sometimes we do, as in Panini's mechanism of anuvṛtti, when parts of previous sutras are tacitly read into subsequent ones. Anuvṛtti is doing similar work to that done by parentheses. So Vasu's translation of Panini uses parentheses in a valid way, I would argue.

What are valid reasons for parentheses? I would say that very, very rarely it is justified to put a Skt word in brackets when not to do so would be seriously confusing or misleading for the typical reader, or when the Skt author is making a tacit point. "He incurred a demerit (karma) by failing to do the ritual (karma)." Or, in the RV, "The lord (asura) of settlements has readied for me two oxen ."(Scharfe 2016: 48).

Then there's the psychology of reading. For me, this is one of the important reasons for not using parentheses or asides of any kind. I've never articulated this before, so what follows may be a bit incoherent. When I watch my mind during reading, I absorb sentences and they create a sense of understanding. It's quite fast, and it's a flow. As I go along, the combination of this flow of sentences and the accumulation of a page or two of it in memory produces the effect of having a new meaning in my mind, of having understood a semantic journey shared with me by the author. But when there are many parentheses, that flow is broken. The reading becomes much slower, and I often have to read things several times, including a once-over skipping the parentheses. This slow, assembly-style reading is not impossible, and one may gain something. But one loses a lot. What's lost is the larger-scale comprehension, and the sense of a flow of ideas.

What I find works for me as a reader and writer is to avoid the branching of the flow of attention while reading. Branching is often done through parenthetical statements, -- and through dashed asides -- (and through discursive footnotes), but not citation footnotes. In my mind, it's like travelling in a car and taking every side road, driving down it for two hundred metres and then coming back to the main road, and continuing just until the next side road, etc. As a writer, I find it quite easy to avoid branching. I do it by thinking in advance about the things I want to say, and then working out a sequence in which I want to present them so that the reader gets the sense of connection. Cut-n-paste is very helpful.

I'm not sure whether the above is totally personal to me, or a widely-shared phenomenon. I've never read anything about this topic. I have read about eye-movements during reading, and the relationship of this to line-length and typeface design. I should look around for material on the psychology of comprehension during reading. There must be something out there.

Wendy Doniger, who writes well, said last year:

I sound out every line I write, imagining the reader reading it, and never imagining as the reader certain scholars, who shall remain nameless, who might be watching with an eagle eye, poised to pounce on any mistake I might make; no, I always imagine the reader as my father, on my side. I try to be that person to my students, who are otherwise vulnerable to an imaginaire of hostile reception that can block their writing, as it keeps some of my most brilliant colleagues from publishing. My father saved me from that.

-- Scroll.in "A Life of Learning"

References

- Eco, U. Mouse or Rat: Translation as Negotiation. Phoenix Press, 2004

- Garzilli, E. (Ed.) Translating, Translations, Translators from India to the West. Cambridge, MA, Harvard Univ., 1996.

- Scharfe, H. "Ṛgveda, Avesta, and Beyond—ex occidente lux?" Journal of the American Oriental Society, 2016, 136, 47-67.

- Venuti, L. The Translator's Invisibility: A History Of Translation. London, New York, Routledge, 1995

Wednesday, March 16, 2016

Re: Against the petition against Pollock

A petition that started this business was posted on change.org. I noticed it on 26 Feb.

The background causative issues include present government policies in India towards national culture, and the publication of the book by Rajiv Malhotra (USA) called The Battle for Sanskrit. I haven't seen the book, but it appears to be an attack on Sheldon Pollock's scholarship. Malhotra is a rich American who funds attacks on American scholars of Indian studies etc.

My response to the petition was posted to the INDOLOGY forum on 27 Feb.:

Some media responses:- https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2016/03/01/scholars-india-demand-harvard-u-press-drop-its-well-respected-editor

- http://www.telegraphindia.com/1160302/jsp/frontpage/story_72368.jsp

- http://thewire.in/2016/03/02/what-the-petition-against-the-sanskritist-sheldon-pollock-is-really-about-23357/

- http://scroll.in/article/804323/make-in-india-and-remove-sheldon-pollock-from-murty-classical-library-demand-132-intellectuals

- http://dsanghi.blogspot.ca/2016/02/murty-classical-library-petition-to.html (former Dean of Academic Affairs, IIT Kanpur)

- http://thewire.in/2016/03/10/swadeshi-indology-and-the-destruction-of-sanskrit-24450/

- http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/services/education/rohan-murty-says-american-indologist-sheldon-pollock-to-stay/articleshow/51231553.cms

- https://networks.h-net.org/node/22055/discussions/116106/controversy-over-editorship-south-asia-classical-translation

- http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/lead-article-by-ananya-vajpeyi-why-sheldon-pollock-matters/article8361572.ece

Friday, February 05, 2016

Babylonians used geometrical methods, 350-50 BCE

"Ancient Babylonian astronomers calculated Jupiter’s position from the area under a time-velocity graph" / Mathieu Ossendrijver

Abstract

The

idea of computing a body’s

displacement as an area in time-velocity

space is usually traced back to 14th-century Europe. I show that in four

ancient Babylonian cuneiform tablets, Jupiter’s displacement along the

ecliptic is computed as the area of a trapezoidal figure obtained by

drawing its daily displacement against time. This interpretation is

prompted by a newly discovered tablet on which the same computation is

presented in an equivalent arithmetical formulation. The tablets date

from 350 to 50 BCE. The trapezoid procedures offer the first evidence

for the use of geometrical methods in Babylonian mathematical astronomy,

which was thus far viewed as operating exclusively with arithmetical

concepts.

BBC Report

Previously, the origins of this technique had been traced to the 14th Century.

The new study is published in Science.

Its author, Prof Mathieu Ossendrijver, from the Humboldt University of Berlin, Germany, said: "I wasn't expecting this. It is completely fundamental to physics, and all branches of science use this method."

For the rest of the BBC report, see:

Wednesday, January 27, 2016

Primitive Man

Greater lack of cultural values than that found in the inner life of some strata of our modern population is hardly to be found anywhere.

-- Franz Boas, The Mind of Primitive Man (2ed, 1938), p.198.

Friday, January 15, 2016

Cranial surgery on Bhoja

Bhojadeva Bhiṣajām

The king cleansed his head at a tank, but a baby goldfish (śaphara-śāvaḥ) got into his skull. Physicans couldn't cure the pain, so the king prepared to die, and banished all the physicians from the kingdom, throwing their medicines into the river.

Indra told the Aśvins about this, and they went to the king's court, disguised as brahmans. They make the king unconscious with moha-cūrṇa and took his skull out and put it in a skull-shaped basin. They removed the fish and threw them into a dish. They reassembled his skull with glue, and woke him up with a reviving medicine (sañjīvanī) and showed him the fish.

Saradaprosad Vidyabhusan (ed.) भोज-प्रबन्धः श्रीबल्लाल विरचितः The Bhoj-Prabandha of Sree Ballal (With English Translation) (Calcutta: Auddy & Co., 1926), pp. 222-228.

See also the tr. by Louis Gray in the AOS series, New Haven, 1950.

The Bhojaprabandha Ballāladeva of Benares, apparently 16th century (so not to be confused with Ballālasena the father of Lakṣmaṇasena, ruler of Bengal).

The king cleansed his head at a tank, but a baby goldfish (śaphara-śāvaḥ) got into his skull. Physicans couldn't cure the pain, so the king prepared to die, and banished all the physicians from the kingdom, throwing their medicines into the river.

Indra told the Aśvins about this, and they went to the king's court, disguised as brahmans. They make the king unconscious with moha-cūrṇa and took his skull out and put it in a skull-shaped basin. They removed the fish and threw them into a dish. They reassembled his skull with glue, and woke him up with a reviving medicine (sañjīvanī) and showed him the fish.

Saradaprosad Vidyabhusan (ed.) भोज-प्रबन्धः श्रीबल्लाल विरचितः The Bhoj-Prabandha of Sree Ballal (With English Translation) (Calcutta: Auddy & Co., 1926), pp. 222-228.

See also the tr. by Louis Gray in the AOS series, New Haven, 1950.

The Bhojaprabandha Ballāladeva of Benares, apparently 16th century (so not to be confused with Ballālasena the father of Lakṣmaṇasena, ruler of Bengal).

Cleverness and Goodness are a rare combination in a person

From the भोजप्रबन्धः बल्लालसेनेन विरचितम्

मनीषिणः सन्ति न ते हितैषिणो

हितैषिणः सन्ति न ते मनीषिणः |

सुहृच्च विद्वानपि दुर्लभो नृणां |

यथौषधं स्वादु हितञ्च दुर्लभम् ||५८||

Wisdom is knowledge together with goodness. -- S. Wujastyk

मनीषिणः सन्ति न ते हितैषिणो

हितैषिणः सन्ति न ते मनीषिणः |

सुहृच्च विद्वानपि दुर्लभो नृणां |

यथौषधं स्वादु हितञ्च दुर्लभम् ||५८||

Wisdom is knowledge together with goodness. -- S. Wujastyk

Friday, December 11, 2015

Linux Mint swapfile

Getting the swap file working in Linux Mint. Using LVM

sudo /sbin/mkswap /dev/mapper/foobar [e.g., mint--vg-swap_1]

sudo swapon -a

sudo /sbin/mkswap /dev/mapper/foobar [e.g., mint--vg-swap_1]

sudo swapon -a

Monday, December 07, 2015

Brandolini's Law

The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it.

Tuesday, August 18, 2015

Research funding in Canada

Funding sources

- SSHRC (locally pronounced /shirk/). Like the FWF, NEH or the AHRC.

- Killam Fellowships. For Canadians.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Used to fund medical history, but doesn't now. But could perhaps be talked to.

See also

Friday, January 23, 2015

Canada tops the list of yoga interest worldwide

According to Google's metrics on search trends, the keyword "yoga" is searched for more in Canada than in any other country in the world. And within Canada, the top "yoga" locations are Vancouver and then Calgary.

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

GNU Freefont fonts and XeLaTeX

The problem

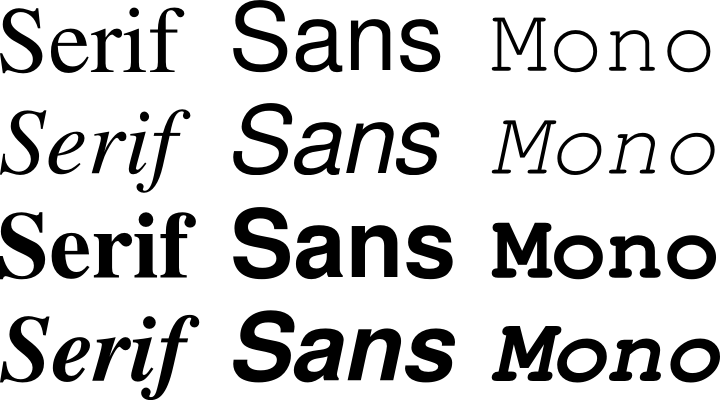

There's been a long-standing issue about using the Gnu Freefont fonts with XeLaTeX. The fonts are "Free Serif", "Free Sans" "Free Mono", and each has normal, italic, bold and bold-italic versions.

These fonts are maintained by Stevan White, who has done a lot of support and maintenance work on them.

These fonts are of special interest to people who type Indian languages because they include nice, and rather complete Devanāgarī character sets in addition to glyphs for

- Bengali

- Gujarati

- Gurmukhi

- Oriya

- Sinhala

- Tamil

and - Malayalam

The Gnu Freefonts are excellent for an exceptionally wide range of scripts and languages, as well as symbols. See the coverage chart.

At the time of writing this blog, December 2014, the release version of the fonts is 4-beta, dated May 2012. This is the release that's distributed with TeXLive 2014, and is generally available with other programs that include or require the FreeFonts.

But the 2012 release of the FreeFonts causes problems with the current versions of XeTeX. Basically, the Devanagari conjunct consonants in the 2012 fonts are incompatible with the current XeTeX compositing engine. (For the technical: Up to TL 2012 XeTeX used ICU; since TL 2013 it's used HarfBuzz.)

In the last couple of years, Stevan has done a great deal of work on the Devanagari parts of the FreeFonts, and he has solved these problems. But his improvements and developments are only available in the Subversion repository. For technically-able users, it's not hard to download and compile this pre-release version of the fonts. But then to make sure that XeTeX calls the right version of the FreeFonts, it's also necessary to weed out the 2012 version of the fonts that's distributed with TeX Live 2014. And that's a bit hard. In short, things get fiddly.

Now, Norbert Preining has created a special TeX Live repository for the Subversion version of the FreeFonts. TeX Live 2014 users can now just invoke that repo and sit back and enjoy the correct Devanagari typesetting.

New warning June 2017:

the procedure below is no longer supported. Don't do it.

WARNING

Be warned that the version distributed here is a development version, not meant for production. Expect severe breakage. You need to know what you are doing!

END WARNING

Here follow Norbert's instructions (as of Dec 2014). Remember to use sudo if you have TeX Live installed system-wide.

The solution. A new TeX Live repository for the pre-release Gnu FreeFonts

Norbert says (Dec 2014):

Here we go:

Please do:

tlmgr repository add http://www.tug.org/~preining/tlptexlive/ tlptexlive

tlmgr pinning add tlptexlive gnu-freefont

tlmgr install --reinstall gnu-freefont

You should see something like:

[~] tlmgr install --reinstall gnu-freefont

...

[1/1, ??:??/??:??] reinstall: gnu-freefont @tlptexlive [12311k]

...

Note the

@tlptexlive

After that you can do

tlmgr info gnu-freefont

and should see:

Package installed: Yes

revision: 3007

sizes: src: 27157k, doc: 961k, run: 19769k

relocatable: No

collection: collection-fontsextra

Note the

revision: 3007

which corresponds to the freefont subversion revision!!!

From now on, after the pinning action, updates for gnu-freefont will

always be pulled from tlptexlive (see man page of tlmgr).

Reverting the change:

In case you ever want to return to the versions as distributed in TeX Live, please dotlmgr pinning remove tlptexlive gnu-freefont

tlmgr install --reinstall gun-freefont

Thank you, Norbert!

Thursday, November 13, 2014

The complicated history of some editions of Buddhaghosa's Visuddhimagga

[This is a lightly-revised version of some posts to the INDOLOGY forum sent in November 2014]

The Visuddhimagga was edited and then published twice in Roman script in the first half of the 20th century. By Caroline A. F. Rhys Davids for the PTS, published 1920 & 1921, and by Henry Clarke Warren for HOS, posthumously published in 1950. Neither edition refers to the other.

The Visuddhimagga was edited and then published twice in Roman script in the first half of the 20th century. By Caroline A. F. Rhys Davids for the PTS, published 1920 & 1921, and by Henry Clarke Warren for HOS, posthumously published in 1950. Neither edition refers to the other.

Some discussion of these editions is offered by Steve Collins in, "Remarks on the Visuddhimagga, and on its treatment of the Memory of Former Dwelling(s) (pubbenivāsānussatiñāṇa)," Journal of Indian Philosophy (2009), 37:499–532.

Warren met Caroline's husband, the distinguished scholar Thomas Rhys Davids, in Oxford in 1884, as stated in Lanman's Memorial

notes, and was greatly influenced by him. Warren's work was done long

before that of Caroline Rhys Davids, since Warren died in 1899. But

why wouldn't Dharmananda Kosambi have mentioned Caroline RD's edition in

his 1927 preface to Warren's? It's understandable that Warren's

brother Edward wouldn't have known about Caroline RD's edition, when he

wrote his pathetic Foreword in 1927, since he was not an indologist.

Why did Warren's edition take 23 years to be printed, even after Kosambi

had finished his editing of the MS? 1950 looks like five years after

the war, which is understandable. But that doesn't explain the twelve

years of inaction before the war (and after the editing). Since Warren

had paid for the HOS to exist, one would have thought some priority

might have been given to publishing his work.

And

why didn't Caroline RD mention Warren's work? Warren had used one of

her husband's manuscripts of the VM, so she would surely have had some awareness of Warren's work. And Thomas Rhys Davids was alive until

the end of 1922, and was aware of his wife's work on the VM, since she

gave him some pages for checking, some time before the end of 1920

(mentioned in her foreword). Caroline RD also knew that Warren had

published a subject analysis of the VM in the JPTS in 1892, although she appears

not to know his article "Buddhaghosa's VM" of the same year, or his

"Report of Progress" on his work on the VM, published in 1894. She

mentions Warren in her afterword on p. 767, but only as the author of

Buddh. in Tr. (1896), which incidentally contains a 50 passages translated from the VM.

I would have expected the translator Ñanamoli

to say something about all this in his translation, but he doesn't. He just

says he's using both editions. Perhaps there are book reviews from the

later 1920s or 1950s that explain matters, I haven't looked yet.

Has

anyone systematically compared the two editions for variants? Caroline

RD's edition is a reproduction of four earlier printed editions, two

from Rangoon, two from Ceylon; Warren worked from MSS, two Burmese and

two from Ceylon. All of Warren's MSS came from sources in the UK, so it must have been

known in England, and certainly to Thomas RD, that Warren was working on this text.

As mentioned, Dharmanand

Damodar Kosambi (not to be confused with his son Damodar Dharmanand

Kosambi) worked on Warren's edition of the Visuddhimagga. Dharmanand's

work was finished in 1911, but the book took until 1950 to appear.

Meanwhile, Dharmanand went back to India, and in 1940 he published in Bombay an edition of the Visuddhimagga in his own name, work that he had begun in 1909. It was based on the same manuscripts as Warren's work, plus reference to two printed editions from SE Asia, perhaps the same as those used by Caroline Rhys Davids. Dharmanand said, in his Preface,

Meanwhile, Dharmanand went back to India, and in 1940 he published in Bombay an edition of the Visuddhimagga in his own name, work that he had begun in 1909. It was based on the same manuscripts as Warren's work, plus reference to two printed editions from SE Asia, perhaps the same as those used by Caroline Rhys Davids. Dharmanand said, in his Preface,

The sources used for the present edition are primarily the same as those employed for

the Harvard edition, consisting of four excellent manuscripts: two

Burmese, two Singhalese. In addition, I have used one printed edition

in Burmese and one in Siamese Characters ; while generally not so good

as the first of the Burmese manuscripts, these contain an occasional

superior reading. To reduce the bulk of this volume, I have omitted all

variants ; the best alternative readings, however, will be given with my

own commentary-in the volume to follow.

So there are three editions of the Visuddhimagga published between 1920 and 1950, with entangled editorial histories:

- Caroline Rhys Davids, 1920, based on 4 printed editions

- Dharmanand Kosambi, 1940, based on 4 MSS and 2 editions

- Henry Clark Warren, 1950, based on 4 MSS

Warren died in 1899, leaving his edition almost complete. Kosambi was invited by Lanman to bring it to a publishable state, which he and Lanman did together, completing that between 1910 and 1911. Nothing then happened for fifteen years. Then Lanman and Kosambi settled some dispute, and Kosambi saw the work through the press in 1926-1927. But the work remained unpublished until 1950 [Preface].

For

his 1940 edition, begun in 1909, Kosambi used the same MSS as Warren

had used 40 years earlier. Two of these MSS were personally procured by

Warren from England, by correspondence with Thomas Rhys Davids and with

Dr Richard Morris [as Lanman says],

and a third was personally lent by Henry Rigg. Did Kosambi really,

separately, gain access to the very same privately-owned MSS? Or were

they still in Cambridge MA when he worked there after Warren's death?

Or did Kosambi use Warren's unpublished text in constituting his own

edition. It is hard to imagine that he would not do so, since the work

was done and lay there before him.

I

should mention that for all these editors it was a matter of importance

that their editions were produced in this or that script. Caroline

Rhys Davids' edition was mainly undertaken in order to produce a

Roman-alphabet version of the pre-existing Burmese- and Ceylonese-script

editions. She showed little engagement with actual text-critical

tasks. Warren was engaged with both text-criticism and with the idea of

transliteration. Warren's edition prints MS readings. Kosambi also

cared about script, producing his edition in Devanagari, thus intending specifically to reach a readership in India. Kosambi also engaged in

text-critical tasks to the extent that he applied Paninian grammatical

thinking to the construal of the text, especially in matters of sandhi.

But Kosambi omitted to print any variants from the manuscripts, which

means that his edition cannot be used as a critical edition, since he

denies the reader the opportunity to think critically about his

editorial choices and their alternatives.

The secondary literature

contains references to an edition of the Visuddhimagga by Dharmanand

Kosambi (and not Warren) published by OUP in London in 1950. I think

this is probably just an error.

Labels:

Buddhism,

Kosambi,

Pali,

Rhys-Davids,

Visuddhimagga,

Warren

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)