Friday, January 15, 2016

Cleverness and Goodness are a rare combination in a person

मनीषिणः सन्ति न ते हितैषिणो

हितैषिणः सन्ति न ते मनीषिणः |

सुहृच्च विद्वानपि दुर्लभो नृणां |

यथौषधं स्वादु हितञ्च दुर्लभम् ||५८||

Wisdom is knowledge together with goodness. -- S. Wujastyk

Friday, December 11, 2015

Linux Mint swapfile

sudo /sbin/mkswap /dev/mapper/foobar [e.g., mint--vg-swap_1]

sudo swapon -a

Monday, December 07, 2015

Brandolini's Law

The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it.

Tuesday, August 18, 2015

Research funding in Canada

Funding sources

- SSHRC (locally pronounced /shirk/). Like the FWF, NEH or the AHRC.

- Killam Fellowships. For Canadians.

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Used to fund medical history, but doesn't now. But could perhaps be talked to.

See also

Friday, January 23, 2015

Canada tops the list of yoga interest worldwide

Tuesday, December 16, 2014

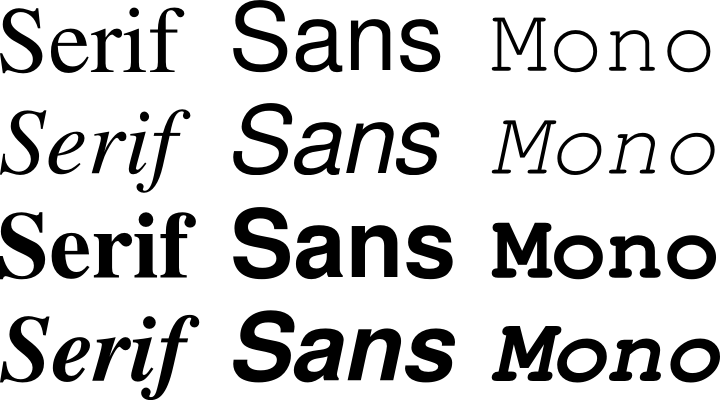

GNU Freefont fonts and XeLaTeX

The problem

There's been a long-standing issue about using the Gnu Freefont fonts with XeLaTeX. The fonts are "Free Serif", "Free Sans" "Free Mono", and each has normal, italic, bold and bold-italic versions.- Bengali

- Gujarati

- Gurmukhi

- Oriya

- Sinhala

- Tamil

and - Malayalam

New warning June 2017:

the procedure below is no longer supported. Don't do it.

WARNING

Be warned that the version distributed here is a development version, not meant for production. Expect severe breakage. You need to know what you are doing!

END WARNING

The solution. A new TeX Live repository for the pre-release Gnu FreeFonts

tlmgr repository add http://www.tug.org/~preining/tlptexlive/ tlptexlive

tlmgr pinning add tlptexlive gnu-freefont

tlmgr install --reinstall gnu-freefont

[~] tlmgr install --reinstall gnu-freefont

...

[1/1, ??:??/??:??] reinstall: gnu-freefont @tlptexlive [12311k]

...

@tlptexlive

tlmgr info gnu-freefont

Package installed: Yes

revision: 3007

sizes: src: 27157k, doc: 961k, run: 19769k

relocatable: No

collection: collection-fontsextra

revision: 3007

From now on, after the pinning action, updates for gnu-freefont will

Reverting the change:

In case you ever want to return to the versions as distributed in TeX Live, please dotlmgr pinning remove tlptexlive gnu-freefont

tlmgr install --reinstall gun-freefont

Thank you, Norbert!

Thursday, November 13, 2014

The complicated history of some editions of Buddhaghosa's Visuddhimagga

The Visuddhimagga was edited and then published twice in Roman script in the first half of the 20th century. By Caroline A. F. Rhys Davids for the PTS, published 1920 & 1921, and by Henry Clarke Warren for HOS, posthumously published in 1950. Neither edition refers to the other.

Meanwhile, Dharmanand went back to India, and in 1940 he published in Bombay an edition of the Visuddhimagga in his own name, work that he had begun in 1909. It was based on the same manuscripts as Warren's work, plus reference to two printed editions from SE Asia, perhaps the same as those used by Caroline Rhys Davids. Dharmanand said, in his Preface,

- Caroline Rhys Davids, 1920, based on 4 printed editions

- Dharmanand Kosambi, 1940, based on 4 MSS and 2 editions

- Henry Clark Warren, 1950, based on 4 MSS

Warren died in 1899, leaving his edition almost complete. Kosambi was invited by Lanman to bring it to a publishable state, which he and Lanman did together, completing that between 1910 and 1911. Nothing then happened for fifteen years. Then Lanman and Kosambi settled some dispute, and Kosambi saw the work through the press in 1926-1927. But the work remained unpublished until 1950 [Preface].

Thursday, August 07, 2014

Linux Mint 17, Cinnamon, Firefox 31 = freeze

Except for the occasional system freezes. This happened usually when I was swapping between windows (alt+tab), and required a re-login.

I've spent some time looking around the web and trying to diagnose the problem. I've found one change that seems to have cleared up the problem, and I am not aware that anyone else has mentioned it yet. I've uninstalled Firefox (31), and replaced it with Google Chrome. I haven't had a freeze since doing that. Fingers crossed.

Wednesday, July 09, 2014

Kuṭipraveśam rasāyanam

Two accounts of a parallel therapy occur in Caraka's Compendium (Carakasaṃhitā). In one version, the patient akes Soma and spends six months naked in a greased barrel (6.1.4-7). In another, he enters a hut, as in Suśruta's account, but Soma is not involved. (See Roots, 2003: 76--8.)

In my discussion in Roots, I drew a parallel with the Aitareyabrāhmaṇa 1.3 in which a Soma ritual involving rebirth is described (the passage was kindly pointed out to me by David Pingree).

Now I have identified another passage that seems to be about the same ritual.

Pātañjalayogaśāstra (sūtras and bhāṣya)

In the Pātañjalayogaśāstra (i.e., the Yoga Sutras and the Bhāṣya commentary, all by Patañjali), there is a sutra that lists the means by which super powers may be attained. Sutra 4.1 says:super powers (siddhi) come from birth, drugs, mantras, asceticism, and meditative integration (samādhi)(janmauṣadhimantratapaḥsamādhijāḥ siddhayaḥ).Explaining this, Patañjali (not Vyāsa) says, in his Bhāṣya,

by using drugs means using rejuvenations (rasāyana) in the houses of the Asuras, and so on.No further explanation is given, and we are left to wonder what the "houses of the Asuras" might be.

(oṣadhibhir asurabhavaneṣu rasāyanenety evamādiḥ).

Śaṅkara

The commentator Śaṅkara, in his Vivaraṇa, expands on this passage in a significant way. He says (1952 edition, pp. 317-18):oṣadhibhir asurabhavaneṣu rasāyanena somāmalakādibhakṣaṇena pūrvadehānapanayenaiva/

by means of drugs in the houses of the Asuras by elixir, by consuming Soma, emblic, and so on, completely without the removal of the previous body.

[I am grateful to Philipp Maas for improving this translation. -- October 2016]The use of the word "soma" suggests that this commentator is putting together the idea of rasāyana entioned in the Bhāṣya with the specific rasāyana treatment described by Suśruta (and, more briefly, Caraka).

Asurabhavana

The only place that Asurabhavana "home of the Asuras" is mentioned with any regularity is in the Pāli literature of the Buddhist Canon. For example, in the Mahā Suññata Sutta (Majjhimanikāya 122/3, tr. by Piya Tan; tr. by Thanissaro Bhikkhu), the Buddha is described worrying about the fact that worldly people live in too-crowded conditions for proper meditation. Asura bhavana is described as being ten-thousand yojanas wide, and is included in a listing of the various parts of the universe where living creatures live (and are crowded). Asurabhavana is therefore a geographical location in the Buddhist universe.In one of the British Library Stein Tibetan manuscripts, IOL Tib J 644, Vajrapāṇi is described entering an Asura Cave in order to meditate. See J. Dalton and Sam van Schaik (2006), Tibetan Tantric Manuscripts from Dunhuang: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Stein Collection at the British Library. Brill, Leiden, Boston, p. 291.

Vācaspatimiśra

Explaining Patañjali, the commentator Vācaspati (as so often) is guessing at the meaning on the basis of his general knowledge (e-edition at SARIT):oṣadhisiddhim āha --- asurabhavaneṣv iti/ manuṣyo hi kutaś cin nimittād asurabhavanam upasaṃprāptaḥ kamanīyābhir asurakanyābhir upanītaṃ rasāyanam upayujyājarāmaraṇatvam anyāś ca siddhīr āsādayati/ ihaiva vā rasāyanopayogena yathā māṇḍavyo munī rasopayogād vindhyavāsīti/

He states the super power of drugs: "in the houses of the Asuras." Because a human, for a certain reason, who has reached the house of an Asura, is served an elixir by the attractive Asura girls. After taking it, he achieves the state of never aging or dying, and other super powers. Alternatively, by taking elixirs in this actual world, like the sage Māṇḍavya took up residence in the Vindhya mountains through the use of elixirs.

Sanskrit Vidh - On alchemical transubstantiation versus piercing

At Rasaratnasamuccaya 8.94-95 there is a definition of śabdavedha.

that bit of iron is converted into the form of gold etc.

The Bodhinī authors were Āśubodha and Nityabodha (hence the witty title), the sons of Jīvānanda Vidyāsāgara Bhaṭṭacārya, and the Bodhinī was published in Calcutta in 1927. So it's arguable that their interpretation was influenced by nineteenth-twentieth century thought. However, their commentary is very śāstric and elaborate (note the Pāṇinian grammatical parsing, "dhama dhāvane ity asmāt lyuḥ" (>P.1.3.134 and pacādi ākṛtigaṇa). And as Meulenbeld points out, they cite an exceptionally wide range of earlier rasaśāstra texts (HIML IIA 671-2). Their interpretations are based on a close reading of classical rasaśāstra literature. At the very least, one can say that their view represents the understanding of learned panditas in turn of the century Calcutta, that vedha meant pariṇāma, or transmutation.

What this leaves unexplained is whether this is a different IE root than vedh "split, pierce."

Saturday, July 05, 2014

The Origins of a Famous Yogic/Tantric Image (part 2)

In a post in February this year I talked about the origin and spread of the famous "lines of energy" image. I asserted that this image was created by or for Yogini Sunita.

I had a memory of having seen the image reproduced in Mircea Eliade's book, Yoga: Immortality and Freedom, or in one of Daniélou's books. I looked at the issues of Eliade's books available to me, and at Daniélou's

Yoga: Mastering the Secrets of Matter and the Universe, that is on my bookshelf, but the image wasn't there.

Now, I can report that I've solved both these puzzles in a stroke. In the Vienna Indology library last week, I came across an Eliade book that I'd forgotten, Patanjali et le Yoga (Paris, 1962). And look at the cover!

Now, I can report that I've solved both these puzzles in a stroke. In the Vienna Indology library last week, I came across an Eliade book that I'd forgotten, Patanjali et le Yoga (Paris, 1962). And look at the cover!Eliade reproduces the image inside the book:

Eliade captions the image "La matière, la vie, l'esprit." As an aside, I have argued and taught in the past that anyone who says "body, mind and spirit" is reproducing a meme from Western New Age thought, and not anything specifically Indian. The threefold division of Man in the original Sanskrit sources is normally "body, mind and speech."

In the acknowledgements at the back of the book, Eliade attributes this image to Alain Daniélou's "Yoga: Méthode de réintégration (Éditions de l'Arche), pp. 171, 179 et couverture." Eliade doesn't give a date for the Daniélou edition he copied from, but the edition will turn up sooner or later. It was first published in 1951.

|

| From http://www.pranayama-yoga.co.uk/ |

The earliest edition of Yogini Sunita's book that I can find is 1965, and she only arrived in England in 1960, and started her first yoga classes that year, as reported in this newspaper clip.

So perhaps the whole story of this image has a prehistory before Yogini Sunita. Perhaps she reproduced the image from Daniélou, or even Eliade.

Update April 2019

Here's the image in a 1949 English translation of Daniélou's book. The caption says "with permission from 'Kalyan' Corakhour". Kalyan was a well-known Sanskrit and Hindi journal published by the Geeta Press in Gorakhpur since 1926. So the trail now leads to an issue of Kalyan from before 1949. Some issues have been scanned and are at Archive.org.

Update January 2022

Found it! After an afternoon of scanning back issues of Kalyan, I located the image in the 1935 issue:

Unfortunately, the image available in the scan is folded over, so the whole image is not visible. But the visible parts are definitely identifiable as the bottom half of the famous Danielou-Eliade-Sunita image. It's nice to see that it is in negative, which explains why it was negative in the early reproductions. This is a bold idea by the Kalyan illustrator. Later printers have preferred to reverse the image to positive. In the volume, the illustration is on page 560 and illustrates an article by Svāmī Śrīkṛṣṇacalled "प्राणायामविषयको मेरा अनुभव"(My experience in the area of Prāṇāyāma") (pp. 554-561).This issue of Kalyan was dedicated to the theme of Yoga, which is no doubt why it came to Danielou's attention, over ten years later. It contains other interesting illustrations, including pictures on pp. 389-392 copied without attribution from Haṃsasvarūpa's Ṣaṭcakranirūpaṇa (Muzaffarpur, Bihar: Trikutivilas Press, 1903?). See Wujastyk 2009: 201-204 for further background on this work

In the same issue of Kalyan, there is an unexpected article on mesmerism and hypnotism by Dr Durgāśaṅkarajī Nāgara, "मेस्मेरिज्म् और् हिप्नाटिज्म्" (pp. 538-544) that gives a history of the techniques, its use at St Thomas's hospital in London, illustrations of magnets and practitioners, and a discussion of electrical flow, the scientific basis, methods of magnetic pass, deep breathing, etc.

Monday, May 19, 2014

Open letter to MLBD about their publishing Mein Kampf

Motilal Banarsidass responded graciously, rapidly and positively to this letter and the petition, and agreed to stop distributing the book.

Friday, March 21, 2014

Notes on the Ukrainian crisis

The Nuland-Pyatt recording

[The following is an extract, authored by me, from the WikiPedia page on this topic. My text has been deleted four or five times by someone with a Russian-sounding name, NazariyKaminski, or by a now-deleted user called RedPenOfDeath and other sock-puppets. So I am placing the text here, for the record.]Friday, February 28, 2014

The Origins of a Famous Yogic/Tantric Image (part 1)

|

| Mark Singleton |

|

| Ellen Goldberg |

Full details of the book can be had from Peter Wyzlic's indologica.de website.

Yogini Sunita's Pranayama Image

|

| Suzanne Newcombe |

Yogini Sunita published a book in 1965 called Pranayama, The Art of

|

| Yogini Sunita's signature |

Yogini Sunita's illustration has been reproduced almost endlessly in books and now on the internet, and there are multiple modifications and interpretations. One of the more common is a negative version, with white lines on a black background. Others are coloured, simplified, and interpreted in various creative ways. It appears in various contemporary yoga-themed mashups. The word प्राणायाम is often masked out. The image is often shown as a representation not primarily of breath control, but of the nodes and tubes of the spiritual body (cakras and nāḍīs).

Yogini Sunita's illustration has been reproduced almost endlessly in books and now on the internet, and there are multiple modifications and interpretations. One of the more common is a negative version, with white lines on a black background. Others are coloured, simplified, and interpreted in various creative ways. It appears in various contemporary yoga-themed mashups. The word प्राणायाम is often masked out. The image is often shown as a representation not primarily of breath control, but of the nodes and tubes of the spiritual body (cakras and nāḍīs). Suzanne Newcombe describes how Yogini Sunita's early death meant that her methods and ideas did not spread as widely as those of other 20th century yoga teachers. Nevertheless, the Pranayama illustration from her 1965 book has become one of the most widely-known images of yoga in the 21st-century (Google images).

Update, July 2014: now see part 2 of this article

Thursday, January 30, 2014

How To Fix A Non-Bootable Ubuntu System Due To Broken Updates Using A LiveCD And Chroot

----

How To Fix A Non-Bootable Ubuntu System Due To Broken Updates Using A LiveCD And Chroot

// Web Upd8 - Ubuntu / Linux blog

If your Ubuntu system doesn't boot because of some broken updates and the bug was fixed in the repositories, you can use an Ubuntu Live CD and chroot to update the system and fix it.

1. Create a bootable Ubuntu CD/DVD or USB stick, boot from it and select "Try Ubuntu without installing". Once you get to the Ubuntu desktop, open a terminal.

2. You need to find out your root partition on your Ubuntu installation. On a standard Ubuntu installation, the root partition is "/dev/sda1", but it may be different for you. To figure out what's the root partition, run the following command:

sudo fdisk -l

This will display a list of hard disks and partitions from which you'll have to figure out which one is the root partition.

To make sure a certain partition is the root partition, you can mount it (first command under step 3), browse it using a file manager and make sure it contains folders that you'd normally find in a root partition, such as "sys", "proc", "run" and "dev".

3. Now let's mount the root partition along with the /sys, /proc, /run and /dev partitions and enter chroot:

sudo mount ROOT-PARTITION /mnt

for i in /sys /proc /run /dev; do sudo mount --bind "$i" "/mnt$i"; done

sudo cp /etc/resolv.conf /mnt/etc/

sudo chroot /mnt

Notes:

ROOT-PARTITION is the root partition, for example /dev/sda1 in my case - see step 2;the command that copies resolv.conf gets the network working, at least for me (using DHCP); if you get an error about resolv.conf being identical when copying it, just ignore it.

Now you can update the system - in the same terminal, type:

sudo apt-get update

sudo apt-get upgrade

Since you've chrooted into your Ubuntu installation, the changes you make affect it and not the Live CD, obviously.

If the bug that caused your system not to boot is happening because of some package in the Proposed repositories, the steps above are useful, but you'll also have to know how to downgrade the packages from the proposed repository - for how to do that, see: How To Downgrade Proposed Repository Packages In Ubuntu

Originally published at WebUpd8: Daily Ubuntu / Linux news and application reviews.

----

Shared via my feedly reader

Monday, January 20, 2014

Fwd: Work Flows and Wish Lists: Reflections on Juxta as an Editorial Tool

From: Dominik Wujastyk <wujastyk@gmail.com>

Date: 18 January 2014 21:58

Subject: Work Flows and Wish Lists: Reflections on Juxta as an Editorial Tool

To: Philipp André Maas <Philipp.A.Maas@gmail.com>, Alessandro Graheli <a.graheli@gmail.com>, Karin Preisendanz <karin.preisendanz@univie.ac.at>, Dominik Wujastyk <wujastyk.cikitsa@blogspot.com>

Shared via my feedly reader

Wednesday, January 15, 2014

Zooniverse and Intelligent Machine-assisted Semantic Tagging of Manuscripts

Once there's a critical mass of digitized Sanskrit manuscripts available, I think it would be very interesting to contact the people at Zooniverse and discuss the possiblility of a Sanskrit MS-tagging project, like the War Diaries.

Tuesday, December 17, 2013

Tools for cataloguing Sanskrit manuscripts, no.1

In the post-office today I saw this piece of board that's used as a size-template to quickly assess which envelope to choose. This is a formalized version of the same tool that I used for the many years that I spent cataloguing and packing Sanskrit manuscripts at the Wellcome Library in London. I made a piece of board with three main size-outlines, for MSS of α, β, γ sizes. Anything larger than γ counted as δ. Palm-leaf MSS were all ε.

It was nice to see the same tool being used for a similar job, in an Austrian post-office!

Friday, December 13, 2013

Thursday, December 12, 2013

From Gnome to Cinnamon

Gnome 2 and 3

|

| Ubuntu with Gnome 2 |

|

| Ubuntu with Unity |

Gnome 3

Gnome 2 and Unity both had their virtues and their flaws. The six-monthly upgrade cycle ("cadence") was never as smooth as it should be, so there have often been niggles that lasted a few weeks or months. I didn't like Unity's two different search boxes. |

| Ubuntu with Gnome 3 |

The biggest boo-boo in the development of Gnome from version 3.8, was fooling with the default file-manager, Nautilus. Many people have complained about the stripping out of function, like split-screen, and that was bad enough. So was the nonsense about shifting the menus to the panel bar (or not!). But what hasn't got mentioned so much (at all?) is that the new Nautilus changed all the keyboard shortcuts and rearranged the shortcuts relating to the menu system. So Alt-F didn't bring up a "File" menu any more, for example. Right mouse-click+R didn't begin renaming a file. If one uses computers all day, then one's fingers get trained, and no interface designer should mess with that stuff without expecting backlash. With Nautilus 3.8, it was like being a beginning typist again, looking at my fingers, chicken-pecking for keys.

I liked the general design model of Gnome 3, with the corner switch to the meta level for choosing programs, desktops, and so on. Searching for lesser-used programs with a few keystrokes rather than poking hopelessly through nested menus. Much better. A genuine and valuable contribution to the vision of how a computer should work.

Thanks to Webupd8, I was able to work around the Nautilus problem by uninstalling it and using Nemo instead.

But things just kept going wrong. The shell crashed too often. On two of my machines it stopped coming up at login, and had to be started manually. Only after a couple of weeks did I track this down to a bad file in ~/.config/gnome-session (and I'm still not 100% sure). Frequent crashes of the gnome-control-panel and other utilities. More and more extraordinary tweaking to make it comfortable and useable. Finally, I've had enough.

Cinnamon

|

| Ubuntu with Cinnamon |